Outside the Paradigm

Share

by Rhys Jones.

Early on in Susanna Clarke's Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, one of the titular characters established the difference between "books of magic and books about magic." This isn't just a rhetorical device by Clarke to advance her narrative. Similar distinctions emerged in various sciences and social sciences and the scholars who write "about" them.

The history of science was probably the first discipline to make this distinction. Because the sciences have their own practices, nomenclature, theories, and, indeed, language (try understanding physics que physicist without knowing calculus), it seemed proper that only academically trained scientists should write the history of science. Thus, the hugely popular and influential Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S. Kuhn, who was a Harvard PhD physicist, was an explanation by a physicist about how intellectual change happens within the discipline of physics. However, the rest of us read Structure, and said, "oh yes, that sort of thing happens all the time in all manner of human activity…." But what we have not properly understood is the distinction between Kuhn (as a trained physicist writing about physics) and us as lay researchers seeing analogies in other fields as the distinction between internalists and externalists – books of physics and books about physics – books of magic and books about magic.

If, from my above explanation, you understand how Kuhn was an internalist, then an externalist would explain intellectual change in the history of physics by understanding the lives, social circumstances, and beliefs of the physicists. Probably the best example would be Albert Einstein who famously dismissed quantum mechanics with the phrase "God does not play dice." Einstein's foundational faith in the prime Deity prefigured what he was willing to accept as truth in the discipline of physics. The externalist, in other words, does not need to have the esoteric knowledge of the physicist to explain the history of physics.

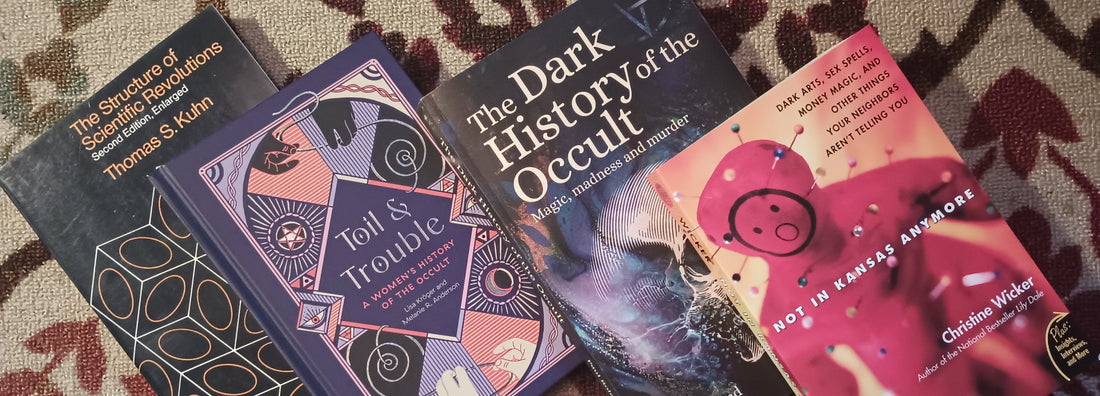

And in magic, we can see also the same approaches. Many books "about" witches and pagans abound that won't tell you the first thing about how cast a circle. I'll mention three. First is Toil and Trouble: A Women's History of the Occult by Lisa Kröger and Melanie R. Anderson, two English Ph.D.'s who like to write about horror topics but also don't put their esoteric credentials (if they have any) forward. Second, is Paul Roland's The Dark History of the Occult which tries to lay at the door of Satanism all manner of occult practice (including rock music) while at the same time disavowing the existence of the dark one. Roland is himself a musician and writer who places his contributions to gothic-psych-baroque steampunk music over any occult association (he doesn't mention any on his webpage). And last, and probably my favorite of the group is journalist Christine Wicker's Not in Kansas Anymore, which explores just how prevalent modern (or neo-) paganism has become. From the waitress at the diner who wears a pentacle to the occult practices of "mainstream" philosophers (like Newton and Hegel) to the popularity of vampires and werewolves, and all the hoodoo folk customs and finance spells people do in the privacy of their own homes/cars/minds, Wicker shows us that paganism and witchcraft is pretty much more out now than ever before.

And while these books are exploring the burgeoning explosion of current witchiness, none of these books are what anyone would consider to be books of the occult. More bluntly, these are not books of shadows.

What about the internalists in magic – the occultists who are writing the history and practice of occultism? More to come on that ….